By Maxime Chouinard

William Steuart Trench is a familiar – and often infamous – name for those who study 19th century Irish history, and more precisely the period following the Great Famine. Born in 1808 in Ballybritas, Trench went on to study and become a land agent. Members of this profession were in good part responsible for enforcing the policies which, among many other things, inflamed the social fabric of Ireland after the misery of an Gorta Mór. Trench was no stranger to this, and though he managed some positive things in his career, his practice drew the ire of many ribbonmen who tried to assassinate him on multiple occasions.

Regardless of Trench’s track record, the man is most famous for his writings on the Irish working class. In this article, I will examine a scene from one of his later stories, « The killin of Timmy O’Brien » which was the fifth story in his uncompleted series « Sketches of life and character in Ireland ». This was published in « Evening Hours Volume II », in 1872, the year Trench passed away.

As with any such story, one must keep a very critical eye as it is never made clear where the author’s creative license begins or ends, or even if the story ever took place at all. We must also keep in mind the viewpoint and intention of Trench in writing such a story, as well as the time that separates this possible memory from the actual writing. Also, please do keep in mind that this is first and foremost a work of fiction. The events are likely inspired by what Trench saw, but this is not an account of an actual encounter, and the characters involved should be understood as imaginary. Any attempt to link this story to real individuals should be looked at with a high degree of skepticism.

That said, it is entirely possible to compare the elements of this tale to what we know of bataireacht in order to judge its value as a source on the practice of this martial art. I have highlighted the elements I found most interesting and will talk about them below.

To read the complete story, follow this link to the Evening Hours.

But he was scarcely outside when a shrill whistle was heard, so loud, long, and piercing, that in a moment the shouts of laughter were hushed, and a dead silence ensued. In less than half a minute, and before the guests could recover their surprise at the strange piercing whistle which, “wild as the screams of the curlew”, rang through the hall, the festive scene of revelry and rout was changed to one of violence and blood. MacEgan, followed by four stalwart young men, all of them with formidable shillelaghs in their grasp, sprang into the room. For a moment he stood still, looking rapidly round him amongst the guests, when his eye suddenly lighting upon the bridegroom, three strides brought them face to face, and immediately within reach of each other.

But the bridegroom was not wholly unprepared. He had risen from his seat as soon as MacEgan entered, and drawing a pistol from his pocket, which he held lowered in his hand; the two young men stood still for a moment glaring at each other.

“Will ye give her up?” shouted MacEgan, in a voice of thunder.

“Never! replied Murphy. “Never: to the likes of you!”

“Then take that!” cried MacEgan; and suddenly raising his knotted stick, he aimed a desperate blow at his rival’s head.

But Murphy was not taken unawares. Though unarmed with a like weapon, he knew how to handle his shillelagh quite as well as MacEgan; and raising his left arm in a slanting position he parried the blow, so that it came down harmless on his shoulder.

“Stand back!” cried Murphy, whose temper was now roused, and who was by no means deficient in pluck; “Stand back, MacEgan; if you advance another inch, or again raise your stick, you are a dead man!” And so saying he cocked and raised the pistol to level with MacEgan’s breast.

“We will see that!” replied MacEgan between his teeth; and again grasping his stick, and whirling it round for another onslaught, Murphy suddenly brought the pistol to a level with MacEgan’s head, and pulled the trigger! A sharp snap was the result. The pistol had missed fire! MacEgan’s eye glistened with triumph; and whirling his shillelagh round his head once more, with a sound like the flight of a bird in the air, he brought it down with such force right over the bridegroom’s forehead as to break through all his defences, and Murphy in a moment lay bleeding an prostrate upon the floor.

“Hah! Shillelagh will never miss fire!” cried MacEgan.

The astonished guests were so taken by surprise, that they stood staring at the combatants in mut wonder at the scene which had so unexpectedly come before them. The priest was first to speak.

“MacEgan,” he said, “ye shall answer this before God and man. Seize him boys; why don’t ye! Down with him, arrest him, – take him in any way ye can! Dead or alive, let him never leave the room that way.” Andadvancing upon MacEgan with the thronged whip in his hand, he called on the guests to help him. A wild tumult now arose; the young men leaped across the tables to arrest and seize MacEgan, while the women shrieked, and clapping thir hand, shouted, “Murder! Murder! Robbers!”

MacEgan never moved: he stood perfectly still, glaring on the thickening crowd, and waiting, shillelagh in hand, for the first men to approach or touch him. All hesitated; when his voie was heard clear and form amidst the tumult.

“Carry her off, two of ye! Let two more clear the course, and spare no man who lays a hand on either ye or her. Away with her I tell ye! I can fight my own battle myself.”

In a moment the bride was lifted in the arms of two able young men, who had entered the room along with him, whilst the two others, making vigorous use of their blackthorns, struck right and left at all who impeded their course; and before the people outside coul in the least comprehend the transactions which had so rapidly passed within the hall, the bride was seated on a pillion behind one of her rescuers, whilst the other sprang upon a horse ready prepared beside her, and away they galloped before the crowd who had collected could in the least comprehend what it as all about!

“They’ll’s have fleet steeds that follow, quoth young Lockinvar.”

But MacEgan was now hard pressed inside the banqueting hall. The Murphys and their friends and faction soon rcovered from their surprise, and though none dare approach MacEgan within the stroke of his shillelagh, yet they seized knives and forks, and hurled them, with bottles and tumblers, at his head. MacEgan received many severe cuts and blows, but he still kept his enemies at bay, so that none dare lay a hand on him, and wheeling, with the dexterity of a hawk upon the wind, and striking down now one and now another of his opponents, as they came within reach of his formidable weapon, he kept retreating all the time towards the door. Just as he came close to it, it was pushed violently open,and Jim the Gaffer, at the head of a dozen able stickmen, bounded into the room.

The guests stood aghast before this wild and sudden reinforcement.

“Who dar’ lay a hand on the MacEgan?” exclaimed the Gaffer, in a voice of thunder, as he stood glaring on the startled guests. “Who dar’ lay a hand on him, I say? Let him come forward now, and we’ll see if he’ll e’en stretch it out again!”

Having cast a look of contemptuous defiance upon the startled crowd of the Murphys, he retreated with his folowers to the door, having hurried MacEgan into their centre, well knowing that his friend would need his help still more outside. He was not there a moment too soon. The outside followers of the Murphys were by no means a contemptible faction and the bridegroom’s younger brother, a fine spirited young man, suspecting that mischief was in the wind, though he was hardly prepared for it breaking out so suddenly, had now collected his people together, and when MacEgan appeared outside, bleeding from the cuts of the missiles, and panting with his exertions in keeping so many enemies at bay, he was at once set upon by the Murphys’ faction, and though surrounded by the few followers who had accompanied the Gaffer into the dining hall, he was sore beset with the vigorous assault made upon him. But the Gaffer again came forward, and whirling his shillelagh till it whistled over his head, “Whoop! he cried; “MacEgan aboo! To the rescue!” and striking right and left, he soon cleared a space for himself and followers around MacEgan, and the two factions, now tolerably equally matched, as many of the O’Connors had joined the Gaffer, stood sticks in hand, opposite to each other, ready to fight to the death.

There was a momentary pause; when young Murphy, the bridegroom’s brother, was observed pressing through the crowd into the open space between the contending parties.

“MacEgan,” he said, “ye are a villain, and a coward! Ye struck down my brother when he was unarmed, and he lies still senseless in his blood. Come out and fight me now, if ye are a man. Ye have your weapon, and so have I. Come on, I say, and fight me now, if ye dar’.”

The Gaffer then beckoned to the gossoon, who still kept his eyes fixed upon his leader. “Away with you, like the wind,” he whispered, “and get out MacEgan’s horse, and have him saddled and bridled outside the orchard wall. If MacEgan kills him, as he surely will, it will take all we can do to get Machome and alive. Away with you now, don’t lose a minnit, for its not long before MacEgan will have him down; and mind you have Mr. O’Connor’s own mare beside him.”

The boy cast a longing look toward the combatants as if he were sorely disappointed at not seeing the fight; but he did not hesitate, and away he went to prepare the horse for MacEgan’s flght, if he should come off victorious.

Meanwhile the two combatant striped to their work. Both of them were able powerfulf young men; but MacEgan appeared to have the advantage in size. Each threw aside his coat and his waistcoat, tied a handkerchief round his waist, loosened his shirt collar at the neck, and advanced towards is opponent with the caution and guardedness of an experienced swordsman who knew that he was about to engage with a foeman worthy of his steel.

It was evident to the numerous and experienced stick-men around, who now looked upon this duel with the most intense interest and excitement, that though MacEgan was the stronger man, Murphy was the most accomplished fencer; and in the feints, parrys, and strokes, which took place, so dextrous and rapid were his hits, that he more than once drew blood from the head of his antagonist. The clatter and rattle made by those two single-stick-men was marvellous; and no one who was not an actual spectator of the scene could have believed, judging from the noise alone, that only two men were engaged in the combat. MacEgan at length, stung by the pain of the wounds he had received, and still more by the cheers and taunts of Murphy’s backers, who claimed the credit of first drawing blood, and finding all his efforts fruitless to break down his opponent’s guard, lowered his weapon and stood still for a moment to regain his breath and take better measure than he had yet time to do of his antagonist’s strength, as well as wonderful skill in the handling of his shillelagh: his example was instantly followed by young Murphy, and the two young men stood opposite to each other, both of them with their sticks lowered, both of them panting and almost quite out of breath, but both of them as determined as ever to continue their desperate conflict.

“Ye are a good stick-man,” said McEgan at last, half-laughing, and half-grinning, through his teeth, as the blood trickled down his face. “ I honour ye for it; but faix I thought I’d have ye down before now.”

“I have met my match an way this time,” replied young Murphy, smiling good humouredly, as he wiped the sweat off his brow with his shirt sleeve.

“Where did ye larn it?” said MacEgan, “ I did not think there was such a man between Shannon and the ‘Devil’s-bit.’”

“Troth then ye’ll hardly believe me when I tell ye that what little I know I learned in London,” returned Murphy, “ there’s a chap there would poke your eye out with his stick in one minute, and put it in again with the self-same stick in the next, so that ye would hardly feel it, or know it was out at all!”

Whilst this strange colloquy was going on the two combatants had partially regained their breath. But just as they were about to raise their sticks to begin the fight once more, a shout was heard from a distant voice behind the immediate crowd of spectators.

“Hah! MacEgan’s bet, I say: he was the first to lower the stik, and cry mercy, and now he’s beggin’ his life. Down with him, I say, and all his bloody brood: let not one of them leave the ground alive! How dar’ he come here to put a stop to a peaceful weddin’!”

“Ye are a liar!” shouted the gaffer at the top of his voice: “the MacEgan never yet cried mercy to livin’ man. Come round here yourself, if ye are not satisfied with what fightin’ is goin’ on already, and I’ll warrant I’ll give ye enough to do.”

So saying, the cunning Gaffer, under pretence of seeking for a distant adversary, passed across the combatants, close beside MacEgan, and whispered as he went by, “ Shorten your stick, and close on him: he can’t stand that. I know his fence of old.”

The hint thus rapidly given was not lost upon MacEgan; and the lookers on being evidently impatient for more fighting, and the young men themselves nothing loth, both raised their sticks and entered again upon the struggle.

After a few scientific feints and parries matters again seemed to become serious. Once more blood was drawn by Murphy, and the knuckles of MacEgan’s hand suffered severely. In a moment MacEgan was seen to run down his right hand to the centre of his shillelagh, and grasping it firmly in the middle, he rushed in upon Murphy. He received a severe blow on the head as he did so; but having got inside his guard, he struck rapidly with both ends, – now one and now the other, so as completely to upset and break down all attempts at ordinary scientific fencing. Murphy saw his danger, and being young and active, made several attempts to escape by springing backwards; but in doing so he came against the crowd outside the ring, and his powers of defence were thus completely checked. MacEgan perceived his advantage, and leaping like a tiger upon him, he seized his adversary’s now almost useless weapon, and wrenching it violently out of his grasp, he flung it over his shoulder into the midst of his followers behind him; then springing back a step he once more resumed the full swing of his weapon, and struck his astonished adversary such a blow on the side of his head as sent him reeling on the ground amongst his followers, bleeding profusely at nose, mouth and ears.

A shout now arose from both the contending parties, such as one hears only in Ireland: a wild, half-frantic shout, – a strange mixture or combination between a British cheer and a savage yell. I have heard it very often, but never out of Ireland; and I never herd it yet but what it foretold dangerous mischief from an angry people. No one who heard that shout could tell whether it was one of triumph or of vengeance; but all could tell that it was the forerunner of wild work.

The Gaffer knew this as well or better than any one “Whoop! Hurrah! MacEgan aboo!” he shouted, leaping wildly in the air, wheeling his shillelagh, and making his voice be heard above the din. “ If it’s for fighting it out ye are among ourselves, now that young Murphy is down, we are not the men to baulk ye’er fancy. Draw off your people there, and let us meet man to man on each side; and if we don’t lay ever mother’s son of ye as low as ever macEgan laid young Murphy to-day, ye may say my name is not the Gaffer.

He had scarcely uttered this high-sounding challenge, when he sprang to MacEgan’s side, who stood alone, still panting with his recent exertions, and apparently scarcely conscious that he was the victor in the duel.

1- « raising his left arm in a slanting position he parried the blow, so that it came down harmless on his shoulder. »

This is a rather simple maneuver, but part of Antrim Bata. If you are surprised or caught unarmed, you can use your arm to parry a blow. The key is knowing how to do it, as you cannot quite parry a stick like you would a punch without getting injured.

2- « though none dare approach MacEgan within the stroke of his shillelagh, yet they seized knives and forks, and hurled them, with bottles and tumblers, at his head. MacEgan received many severe cuts and blows, »

Believe it or not, throwing anything you have on hand at your opponent is a part of Antrim Bata, and a very important part of faction fighting in Ireland. During the famous faction fight of Ballyveigh Strand in 1834, witnesses reported how the battlefield appeared as if covered by a dark cloud from all the rocks being thrown.

3- « wheeling, with the dexterity of a hawk upon the wind, and striking down now one and now another of his opponents, as they came within reach of his formidable weapon, »

It is interesting how the description of « wheeling » changes from author to author, and it is important to note that like many facets of bataireacht (and Irish vocabulary as a whole) an action could be described very differently by different people, and regions could have their own take on a common word. This is why I do not ascribe to rigid typologies. In many descriptions of faction fights, wheeling is taken as the whole preparatory actions before the fight; throwing insults, stomping or dancing and flourishing the stick. In this case, it seems to be mostly referring to the latter. What the Gaffer is doing here, seems to be a tactic that we use in Antrim Bata to defend against multiple opponents, that is to use wide circular motions (in our case two-handed) to create a defensive space. This is, of course, one interpretation, the excerpt is not precise enough to really make a fair judgment.

4- « Whoop! he cried; “MacEgan aboo! To the rescue! »

« A shout now arose from both the contending parties, such as one hears only in Ireland: a wild, half-frantic shout, – a strange mixture or combination between a British cheer and a savage yell. I have heard it very often, but never out of Ireland; and I never herd it yet but what it foretold dangerous mischief from an angry people. No one who heard that shout could tell whether it was one of triumph or of vengeance; but all could tell that it was the forerunner of wild work. »

« Whoop! Hurrah! MacEgan aboo!” he shouted, leaping wildly in the air, wheeling his shillelagh, and making his voice be heard above the din. »

This is a very fun and unique part of Irish stick fighting among the martial arts of Europe. While most European fighters preferred to keep fairly silent, the Irish had a propensity for shouting during fights. What our protagonist is shouting here is very classic. « Whoop » or « Whiroo » are very well documented in faction fights, as is the battle cry of « abú » meaning « for ever », or « to victory ». In Antrim Bata, shouts are used a bit like a kiai in kendo. As a way to surprise an opponent and give intent to a strike, but also as a way to disturb an opponent during a fight which we call « bluffing ».

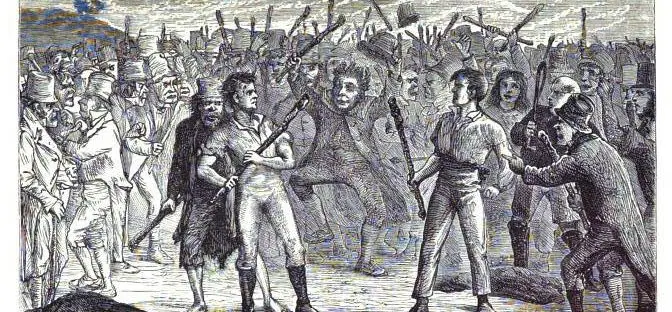

5- « Each threw aside his coat and his waistcoat, tied a handkerchief round his waist, loosened his shirt collar at the neck, and advanced towards his opponent with the caution and guardedness of an experienced swordsman who knew that he was about to engage with a foeman worthy of his steel. »

This part is most interesting as it is often portrayed in illustrations but rarely described. This is an action that is common in weapon duels around Europe, quite possibly to assure the opponent and the onlookers that none of the duelists are wearing any sort of protection or hidden weapons. Which, if you remember one of my previous entries to this blog, could happen and with deadly consequences.

This is something which was also described to me by my máistir. People stuffed their hats and the sleeves of their shirts with cotton, which I believe was also possibly done as a way to train, and sowed implements like fish hooks and blades in their clothes to deter people from grabbing them.

The handkerchief around the waist was probably there mostly to help keep the pants and shirts in place, but it is illustrated in a few paintings and engravings, namely this beautiful piece by Daniel MacDonald from 1844 named « The Fighter ».

Next is the coming on guard, and from there we start to see the profound admiration that Trench seems to give to bataireacht, comparing it to expert fencing. An apt observation from a man who was apparently on the receiving end of a shillelagh more than once in his career.

6- « though MacEgan was the stronger man, Murphy was the most accomplished fencer; and in the feints, parrys, and strokes, which took place, so dextrous and rapid were his hits, that he more than once drew blood from the head of his antagonist. »

It surprises many people, but bataireacht is very often described as « fencing » or « boiscin ». Fencing today is exclusively associated with sword fighting, but the expression at the time covered a wide range of melee fighting from boxing to quarterstaff. The practice of bataireacht and broadsword fencing share many similarities and were probably at some point in time taught conjointly, but they also exhibit fundamental differences. I will develop more on this in a future article.

7- « who claimed the credit of first drawing blood »

This is something I must say I never encountered before, but it is not entirely surprising to see it here as fighting to the first blood was a very widely recognized form of dueling in Europe, though here it is not considered the end goal, but rather more of an honorific achievement. I would like to see it mentioned somewhere else though before considering it an Irish thing.

8- “Ye are a good stick-man,”

According to Niall Ó Dónaill’s dictionary, we could translate this as baitín or bataire.

9- “Where did ye larn it?” said MacEgan, “ I did not think there was such a man between Shannon and the ‘Devil’s-bit.’”

“Troth then ye’ll hardly believe me when I tell ye that what little I know I learned in London,” returned Murphy, “ there’s a chap there would poke your eye out with his stick in one minute, and put it in again with the self-same stick in the next, so that ye would hardly feel it, or know it was out at all!”

This is a very interesting part of this story. It is a documented fact that schools of bataireacht existed across Ireland, and that individuals taught these skills to one another, but it is the first time I see the mention of a fighter saying that he learned his art in another country… and in England of all places! I am sure this will be a contentious claim, and one which could very well be ascribed to the author’s imagination, but it is interesting to examine it.

Did Murphy meet an Irish expatriate in London? Or perhaps did he learn some sort of fencing with a cudgel or with the sword and applied it to his handling of the shillelagh? Based on his description, it could even have been a lesson of foil, as few stick styles that we know of included thrusts.

10- “Hah! MacEgan’s bet, I say: he was the first to lower the stik, and cry mercy, and now he’s beggin’ his life. »

Another interesting tidbit here, as lowering the stick is seen as surrendering. Again, I have not seen this elsewhere and would like to see another mention.

11- « Shorten your stick, and close on him: he can’t stand that. I know his fence of old.”

Now, we get to the most interesting part of the text. It is unfortunately not very well described, and we can only try and interpret it from what we know of bataireacht.

12- « MacEgan was seen to run down his right hand to the centre of his shillelagh, and grasping it firmly in the middle, he rushed in upon Murphy. He received a severe blow on the head as he did so; but having got inside his guard, he struck rapidly with both ends, – now one and now the other, so as completely to upset and break down all attempts at ordinary scientific fencing. Murphy saw his danger, and being young and active, made several attempts to escape by springing backwards; but in doing so he came against the crowd outside the ring, and his powers of defence were thus completely checked. MacEgan perceived his advantage, and leaping like a tiger upon him, he seized his adversary’s now almost useless weapon, and wrenching it violently out of his grasp, he flung it over his shoulder into the midst of his followers behind him; then springing back a step he once more resumed the full swing of his weapon, and struck his astonished adversary such a blow on the side of his head as sent him reeling on the ground amongst his followers, bleeding profusely at nose, mouth and ears. »

There is a lot to unpack here. Now let’s address the short grip first. Most who are familiar with bataireacht will know that one defining aspect of the practice is the grip at the lower third, held this way as to act as a guard for the arm and the head. My first thought that the Gaffer was suggesting to go for a two-handed grip, such as we would do when closing in Antrim Bata or in Rince an Bhata Uisce Bhata, but it really seems that MacEgan only slightly shortens his grip. Like this, he can effectively fight from a closer distance than Murphy. If he manages to break the distance- which he does while receiving a severe blow that luckily for him does not end the fight- and keep Murphy close he can then negate a lot of his opponent’s strikes.

Now, this works because Murphy seems to be specialized at fighting from a distance, which is fine as long as you can maintain it. The size of the fighting area does not allow Murphy to regain control of the distance and so he is overwhelmed. This illustrates the importance of having a well-rounded set of techniques that will allow you to fight in different situations and in different ranges. This is what Antrim Bata teaches. While we try to use our weapon’s reach to its full potential, we also have quite an array of mid and close-range techniques allowing us to adapt our style to the situation at hand.

Next comes the disarm, also an integral part of Antrim Bata and a reason why we keep the stick high and out of reach as much as possible.

Gruesome fact: bleeding from the nose, ears and mouth all at the same time is a sign of a severely fractured skull. The chances of young Murphy’s survival are slim, even more so considering the surgical options of the time.

13- « still panting with his recent exertions, and apparently scarcely conscious that he was the victor in the duel. »

This is a fairly realistic rendition of the end of a fight, especially such a violent and long one which is no doubt taxing.

To conclude, I would say that the description of this fight fits quite well with what we know of bataireacht and the culture around it. The tactics and particularities of the style seem to match what we know, and even go a bit further than what is usually written about them. Whether this whole event sprang from the author’s imagination or was duly recorded is impossible to say, but the depiction of the fight itself is quite realistic and I would dare to say that the author knew what he was talking about for the most part.

If you would like to learn to learn the martial art behind this story, be sure to check the rest of our website to see where you can learn Antrim Bata.

Sie-haben einen fantastischen Blog Dank. Lisabeth Spencer Obeded

J’aimeJ’aime